Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart washingtonpost.com: The Good Book: Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart Go to Chapter One Section

The Good Book Reading the Bible with Mind and Heart By Peter J. Gomes

Chapter One: What’s It All About?

Many years ago when I began my service as minister in Harvard’s Memorial Church, an anonymous benefactor offered to present as many Bibles as were needed to fill the pews. No particular translation was specified, and no objections were made to the Revised Standard Version. Before proceeding too far along the road of this benefaction I felt it wise to take the advice of some colleagues, and I found their reaction to be apprehensive, and in fact quite suspicious of the motivation behind the gift. “What does the benefactor want or expect?” I was asked, and warned that placing Bibles in the pews would create an invitation to steal them. Further, I was warned that “people will think that this is a fundamentalist church. If they see Bibles in the pews you will have an image problem.” My colleagues and counselors meant well, I knew, and wished only to protect the church from secular and religious zealots. These concerns notwithstanding, however, we accepted the gift, placed the Bibles in the pews, and, happily, over the years we have lost quite a few to theft.

A Nodding Acquaintance

One of the more embarrassing social situations, upon which even Miss Manners and other arbiters of social etiquette have failed to provide a useful strategy, is the one in which you have more than a nodding acquaintance with someone. At the point of introduction you got the person’s name, forgot it, asked it again, and forgot it again. Meanwhile you go on meeting this person, chatting and being chatted with, but you have clearly passed beyond the point where you can ask for the name again. It is easy enough to maintain the facade of friendship until that awful moment comes when you are required to introduce your nameless friend to a third party. What to do? I have seen artful evasions such as “Surely you two know each other?” followed by a discreet withdrawal while they got on with the job themselves, leaving you unexposed. Another stratagem is to avoid the risk of introduction altogether by declaring emphatically, “Ah! Here’s an old friend!” What we should know, pretend that we know, and wish that we knew, we don’t. Worse still, we do not know, without risk of embarrassment, how to ask about what we need to know.

This, I suggest, is the way it is with so many people and the Bible. Once, perhaps a long time ago in childhood or in early youth, or even as late as in college, you were introduced. You have a nodding acquaintance with the Bible, or at least you feel you ought to, and you can recognize some familiar phrases, especially if they “sound” like the King James Version of the Bible; yet, to all intents and purposes, the Bible remains an elusive, unknown, slightly daunting book. It is awkward to concede that you don’t know very much about the Bible, given its cultural prominence, and it is difficult to figure out how to get reintroduced without conceding your illiteracy. Perhaps the lament I have heard more and more frequently in recent years is the one that says, “I wish I knew more about the Bible.”

Poll after poll continues to find the Bible atop every best-seller list, and one survey after another confirms the fact that an astonishingly high percentage of American households claims not only to own a Bible, but to read it on a regular basis. Hardly a hotel room in the world is without a copy of the Bible in the bedside table, placed there courtesy of the Gideons; and through the unremitting efforts of the Wycliffe Society the Bible has been translated into nearly every language on earth. There are Bibles for women, Bibles for children, Bibles for Asians, Bibles for African Americans. There are so many translations, paraphrases, revisions, and editions now available, many of which are the products of the last twenty years, that the market for the Bible may well be saturated. In the introduction to their 1983 study of twentieth-century English versions of the Bible, So Many Versions?, Sakae Kubo and Walter F. Specht observe, “Some people are of the opinion that there is a ‘glut’ of translations on the market today. Some feel it is time to call a halt to the work of translation for a while until we absorb the flood of recent translations.”

Despite the ubiquity of the Good Book, it is increasingly clear that the rate of biblical literacy has gone down rather than up. A recent American poll conducted by the Barna Research Group discovered that 10 percent of the sample of more than one thousand persons polled said that Joan of Arc was Noah’s wife, 16 percent were convinced that the New Testament contained a book by the Apostle Thomas, and 38 percent were of the view that both the Old and New Testaments were written a few years after Jesus’ death. These replies are worthy of the old Sunday school howler in which the epistles are defined as the wives of the apostles. The president of the polling firm commented, “Clearly, most people don’t know what to make of the Bible. Adults constantly gave us answers which contradicted or conflicted with previous replies.” It is not that people lie about their knowledge of the Bible; it is that they often feel that in order to maintain their moral credibility they must reply in the affirmative when questioned by pollsters, since most believe that they ought to read it. Many of these modern Christians are much like the Emperor Charlemagne who, it is said, slept with a copy of Saint Augustine’s magnum opus, The City of God, under his pillow in the hope that this passive proximity to a great but difficult work might be of some benefit to him.

Hearing the Word

Hearing the Bible in church presumably helps people become better acquainted with it. In fact, hearing the Bible in church was the way in which most Christians for a thousand years became familiar with scripture, and in most Christian churches today pride of place is still given to the reading of appointed passages from the Bible. In the Anglican and Protestant traditions these readings are called “lessons” because it is believed that they are not merely liturgical acts but have a moral teaching function as well. This tradition of hearing the Bible read aloud in public is as old as Christian worship. When Saint Paul instructs the Christians in the Corinthian church on a suitable order for worship, he tells them: “When you come together, each one has a hymn, a lesson, a revelation, a tongue, or an interpretation. Let all things be done for edification.” (I Corinthians 14:26)

In my naivete as a pastor I thought that this tradition of edification in church was alive and well until I once said as much to a regular churchgoer who every Sunday hears 2 psalm and at least two lessons, one from the Old Testament and one from the New Testament, and has done so for years. Her response caught me up short. She said that listening to the lessons in church was like eavesdropping on a conversation in a restaurant where the parties on whom you are listening in are speaking fluent French, and you are trying to make sense of what they are saying with your badly remembered French 101. You catch a few words and are intrigued, trying to follow, but after a while you lose interest, for the effort is too great and the reward too small. That is a pretty vivid image of a fairly common modern dilemma, and most people find themselves too embarrassed to confess that this is their situation. It used to be said that most Christian adults live their lives off a second-rate second-grade Sunday school education, and that the more they hear of the Bible in church, the less they feel they know about it.

Many people want to do something about their biblical illiteracy. There is something there that they feel they ought to know about, and yet they are frustrated in their attempts to read the Bible and to make sense of it for themselves. Because it is unlike any other book, reading the Bible is an intimidating enterprise for the average person. To remind the reader that the Bible is not a book but a library of books, written by many people in many forms over many years for many purposes, is to further complicate the ambition and add to the frustration. Bound in its authoritative black leather and gilt-edged pages, with, in some editions, the words of Jesus printed in red, the physical artifact of the Bible has a certain aura. Add to this the powers attributed to it, with its designation as “holy” and therefore suitable for use in oath-taking and in sanctifying proceedings both civil and sacred, and the Bible is much more easily reverenced than read.

Inhibitions and Complexities

It is not its status as an icon or holy object, however, that inhibits the reading of the Bible. It is the sense as well that the Bible is a technical book, requiring a level either of piety or of knowledge not available to the average reader. There are also admitted obstacles. What does a person who has no knowledge of the biblical languages, no formal theological training, and no experience in the very technical fields of translation and interpretation do with the Bible? An ancient answer was to submit oneself to those who did possess those qualities. The image of formative Christianity as a “Bible-centered community,” one continual scripture seminar for the faithful, is an appealing one, but totally false. Saint Augustine, for example, opposed Saint Jerome’s heroic project of translating the Greek Bible into the more accessible Latin because making the Bible more accessible would be more likely to cultivate a conceit on the part of those who, because they could understand the language, would now also assume that they could understand the book. Vernacular translations of the Bible were forbidden to those few pre-modern Christians who could read, and English translations of the Bible up to the time of King James’s version of 1611 were generally regarded by the religious establishment as doing more harm than good.

Ironically, it was the tremendous explosion in scholarship about the Bible itself, an enterprise whose highest motivation was to make sense of the Bible and to clarify its complexities, that made it harder rather than easier for the average person to read the Bible with any degree of self-confidence. By the close of the nineteenth century, a period of unprecedented attention to the complexity of biblical scholarship, the frustration of the average reader was represented by no less a figure than Grover Cleveland. In some exasperation, the twenty-second and twenty-fourth president of the United States said, “The Bible is good enough for me, just the old book under which I was brought up. I do not want notes or criticisms or explanations about authorship or origins or even cross-references. I do not need them or understand them, and they confuse me.”

A century later we can understand his frustration and his desire to return to what the scholars call a precritical stage, and in fact many have attempted to do just that. After all, we should not have to be a certified electrician in order to enjoy the benefits of the lightbulb.

Suppose, however, that that lightbulb does little to illumine the dark places in which we find ourselves in these last days of the twentieth century? What are we to do with a Bible about which we know less and less, and which itself would appear to have less and less to say to us in language that we can understand? The question is not a new one. In 1969, in a small book with the provocative title The Strange Silence of the Bible in the Church, lames D. Smart addressed the gap between the fullness of modern biblical scholarship on the one hand, and the poverty of biblical literacy on the other. In an America racked by the intensities of the struggle for civil rights, the battles of the counterculture, and the depredations of the Vietnam War, the Bible seemed unequal to the morally demanding times, and its silence was deafening. How could this be? In his Preface, Smart, a Presbyterian minister and biblical scholar, attempted an answer:

Responsibility for this strange silence of the Bible in the church does not rest upon preachers alone. Much too often they have borne the whole reproach without there being any recognition of the complex character of the dilemma in which they find themselves. Rather, there had been a blindness which scholar, preacher, teacher, and layman alike have shared–a blindness to the complexity of the essential hermeneutical problem, which, in simple terms, is the problem of how to translate the full content of an ancient text into the language and life-context of late 20th century persons.

Contemporary Christians tend to avoid complexity as being hazardous to their faith, and are thus unprepared to cope with complexity when it confronts them. In April 1996, for example, all three major U.S. weekly newsmagazines featured Jesus as the cover story for Holy Week. What was the reason? This was hardly an outbreak of newsroom piety, but rather the “discovery” that scholars were debating yet again the relationship between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith, and that many of the words and actions attributed to Jesus in the New Testament were in fact, in the view of much of modern scholarship, the work of writers of the early Christian movement. “Some scholars are debunking the Gospels,” ran Time’s cover headline. “Now traditionalists are fighting back. What are Christians to believe?”

I was asked by many sincere believers as well as by the vaguely curious what I thought of Time’s story. Would it do damage to the faith? Hardly. As the sign in the old antique shop reads: NOTHING NEW HERE. Questions about the nature of the gospels and of their place in the life of the church are as old as the gospels themselves. Questions about the resurrection are as old as the Apostle Paul’s writings on the subject. These are matters that have always belonged to the church, and always will. Time’s discovery of Christianity’s two-thousand-year-old debate suggests only how far Time is removed from the intellectual life of biblical scholarship. But alas, the story also revealed the large gap between the basic working assumptions of biblical scholarship long held by the scholarly community and the conventional wisdom or general knowledge of a less and less biblically literate Christian population. To make a story there must be winners and losers. The not too subtle implication of this Holy Week Special is that what the scholars believe they know and what the believers believe they believe are seen to be at odds, and if the scholars are right, then the believers must be wrong, and the Christian faith folds like a house of cards.

What Are We Doing?

What can be believed about the Bible? What do we need to know about the Bible? Can the Bible survive the efforts to interpret and understand it? Can we? Is it wrong to ask critical questions of the Bible? How do we reconcile the parts we understand, and perhaps dislike, with the parts we do not understand but which may be salutary? When we speak of the authority of scripture, as certain Protestant traditions delight in doing, does that mean that we suspend all of those faculties of mind and intelligence which we apply to all other books and all other instances of our life? How indeed do we, as James Smart suggested, “translate the full content of an ancient text into the language and life-context of late 20th century persons” without risking our intelligence or the integrity of that text?

Over the years of my ministry in a university and well beyond it, I have come to the conclusion that most sincere Christians are curious in these matters, unlike Grover Cleveland, and want to become better acquainted with the Bible. I am further convinced that the more importance one attaches to the significance of the Bible both for the self and for society, the more one is driven to a consideration of questions which in an earlier day might either have been ignored or left to the competence of the experts. As making sense has as much to do with formulating useful questions as it has to do with developing useful answers, the thoughtful but uninformed reader will want to know how to go about doing both.

The Episcopal Church, while not known as a “Bible” church in the sense of those evangelical and free churches that advertise themselves as such, nevertheless exposes its worshipers to a great deal of scripture on Sunday mornings. There is a movement to do something about biblical literacy among what one social historian of the Episcopal Church has called “God’s frozen people.” Understanding the Sunday Scriptures, a release of Synthesis Publications, is designed to provide help to people who have finally reached the awareness that they need it. The Reverend Dr. H. King Oehmig, editor of the first volume in a series on the Episcopal lectionary, says of it, “The Episcopal Church has more scripture on Sunday than any other denomination in America. After listening to the desires of the people in the pews for a responsible yet inspiring study resource to prepare them to hear the Word on Sunday morning, we have produced this unique resource.”

The United Methodist Church, America’s second-largest Protestant denomination after the Southern Baptists, is also attempting to respond to the felt needs of biblical literacy. It has produced not only a series of books and study aids but a series of films utilizing the most sophisticated of contemporary biblical scholarship. When I asked some Methodist pastors how this worked, nearly all of them were pleased with the results in their churches. The study program is organized into small groups that pledge to meet during the week for nine months, and are meant as bonding fellowships as well as study groups, designed to combine the best elements of the old adult Sunday school class, the Methodist class meeting, the prayer meeting, and the support groups that have become the local units of our secular therapeutic culture. Apparently these groups help in developing a better knowledge of the Bible, and provide an informed lay leadership which enriches the work and the life of the local congregation at the same time. As one of the pastors said to me, “The church is in bad shape when the only person who knows anything about the Bible is the pastor.”

These are clearly new initiatives taken to meet what is generally recognized to be the crisis of biblical illiteracy. We might well ask how this illiteracy came to be, given that the Bible has always had pride of place in Christian worship and particularly in American Protestantism, but any of us who have had experience of what passes for “Bible study” in recent years in most churches can answer that question. For many the Bible served as some sort of spiritual or textual trampoline: You go onto it in order to bounce off of it as far as possible, and your only purpose in returning to it was to get away from it again. It is the lay version of what Willard Sperry, one of my predecessors in The Memorial Church, used to lampoon as “textual preaching.” The preacher who was keen to practice what he preached would follow this formula: “Take your text, depart from your text, never return to your text.”

Bible studies tend to follow this route. The Bible is simply the entry into a discussion about more interesting things, usually about oneself. The text is a mere pretext to other matters, and usually the routine works like this: A verse or a passage is given out, and the group or class is asked, “What does this mean to you?” The answers come thick and fast, and we are off into the life stories or personal situations of the group, and the session very quickly takes the form of Alcoholics Anonymous, Twelve-Step meetings, or other exercises in healing and therapy. I do not wish to disparage the very good and necessary work that these groups perform, for I have seen too many good effects and have known too many beneficiaries of such encounter and support groups to diminish by one iota their benefit both to individuals and to the community. I simply wish to say that this is not Bible study, and to call it such is to perpetuate a fiction.

Bible study actually involves the study of the Bible. That involves a certain amount of work, a certain exchange of informed intelligence, a certain amount of discipline. Bible study is certainly not just the response of the uninformed reader to the uninterpreted text, but Bible study in most of the churches has become just that–the blind leading the blind or, as some caustic critics of liberal Protestantism would put it, the bland leading the bland. The notion that texts have meaning and integrity, intention, contexts, and subtexts, and that they are part of an enormous history of interpretation that has long involved some of the greatest thinkers in the history of the world, is a notion often lost on those for whom the text is just one more of the many means the church provides to massage the egos of its members.

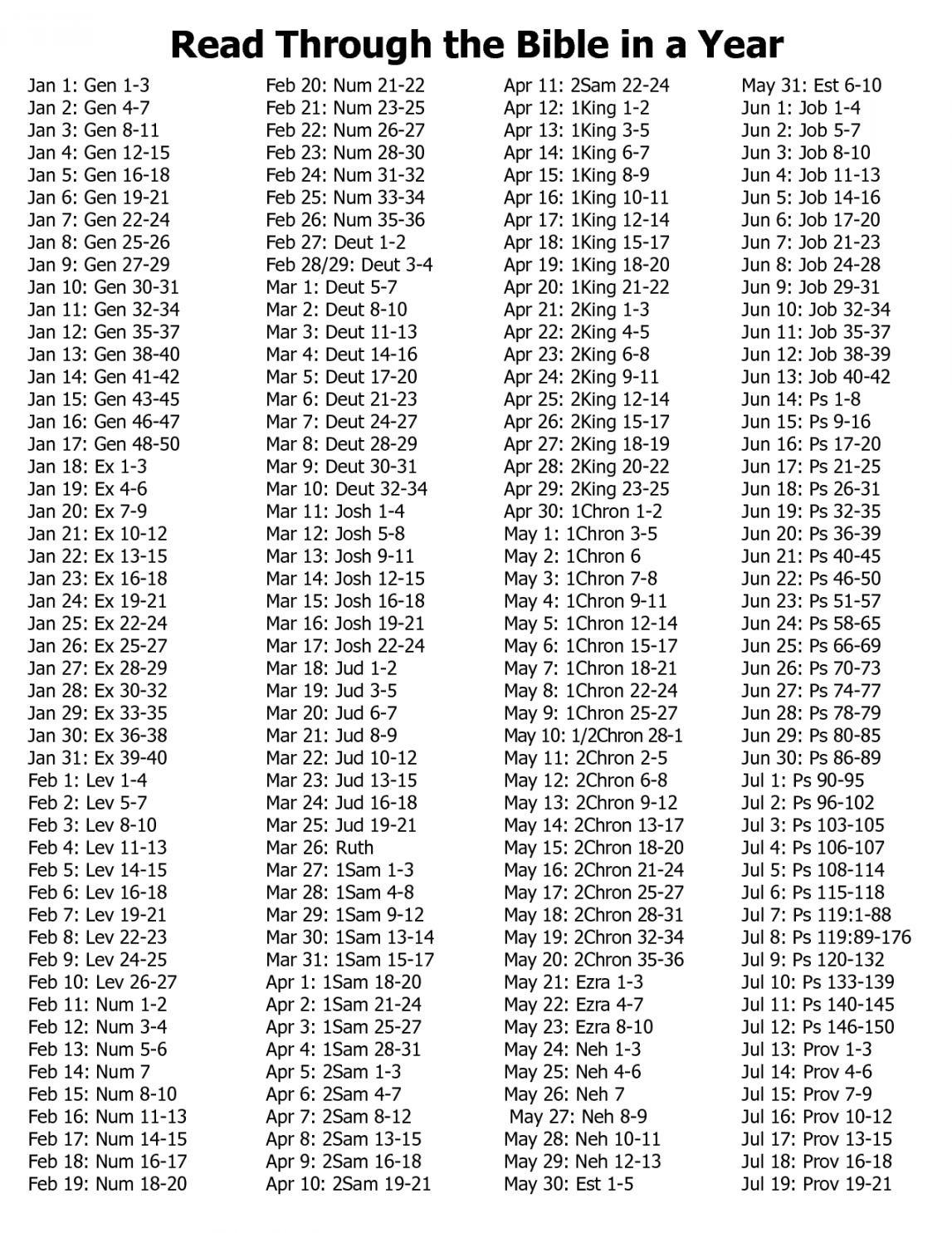

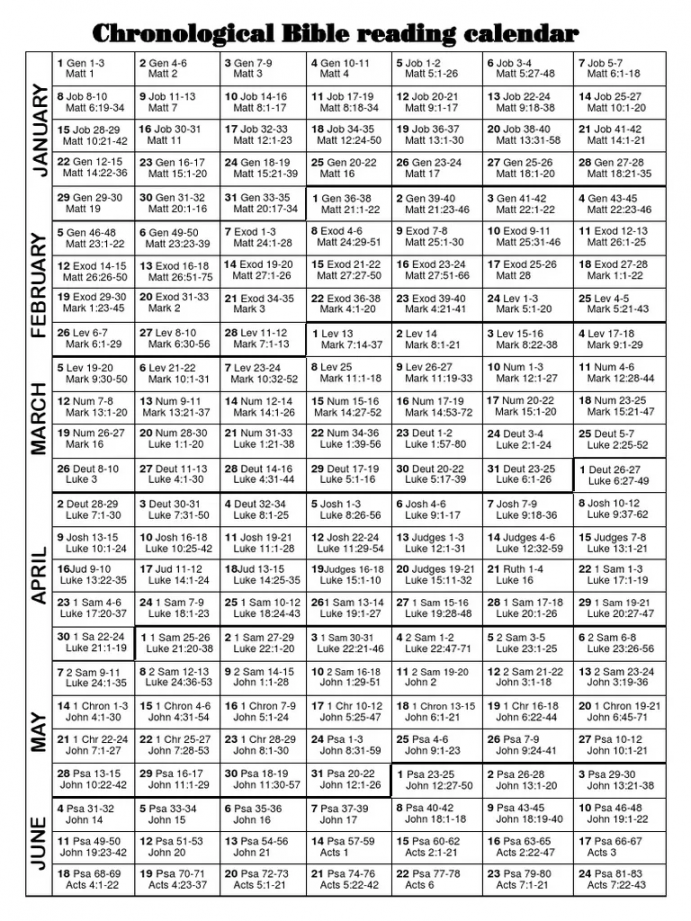

Opening the Bible is the easy part. What to do with it once it is opened is more difficult. At the start of Lent each year, when the time for taking up a Lenten discipline is upon us, invariably a number of people will tell me that they intend to read the Bible from cover to cover. They mean to start at Genesis 1:1 and stop when they get to Revelation 22:21. The enterprise is not as easy as it sounds, and people begin to waver in their resolve when their expectations of narrative inspiration are not sustained by genealogies, codes of Jewish law, and ancient Jewish history. The New Testament is somewhat easier to digest, in part because it is smaller and its subject more easily identified as Jesus and the early church. Nevertheless, it is not always clear what is going on in the Acts of the Apostles; the expectation that the letters of Paul provide a systematic correspondence is often disappointing; and while they find it fascinating, not many know what to make of the book of Revelation. Those who get through usually feel as if they have run a marathon, where the object of the course is to finish and not necessarily to observe the landscape along the way. Those who do not cross the finish line often feel like moral failures who have broken their diet or fallen off the wagon and taken a forbidden drink.

The risks of discouragement notwithstanding, I think there is something to be said for taking on the Bible in this way. It is a bit like total immersion in a foreign language; eventually, if you stick with it, you will get some sense of what is going on, you will see and feel the shapes of the language, and you will acquire a sense of those places to which you wish to return, and those places you wish to avoid. This is not a bad thing.

The Construction of Scripture

The Bible, however, is more than an endurance contest, and one may know better how to make a useful reading of it if one has a sense of what the Bible actually is. At the risk of appearing to offend those who already know what they need to know in this regard, I begin by stressing the fact that the Bible is not a book but a collection of books, in fact, a library of books. Sixty-six separate books have been collected from the writings of ancient Hebrews and early Christians, and by a rational editorial process have been brought together over a period of centuries to form the book we now know as the Bible. The first thing the reader must remember upon encountering the Bible is that it is a result or consequence of a complex process that is both human and divine. The relationship between the human and the divine in this process is an intimate one. These are writings by human beings who are themselves believed to have been inspired by God. It is further believed that it is by the inspiration of God that human agency is given the wisdom and the will to organize these books, and it is believed that through these books the divine word of God is to be communicated. Thus it is not sufficient explanation of the Bible to say simply that it is either the Word of God or “merely” a human book, such as The Iliad or The Odyssey. The Jews who gathered together these books from a whole range of their writings and called them “scripture” did so in the firm conviction that God spoke through these human writings, and that these human writings brought the people of God nearer to God. Thus, when they call the first five books of the Hebrew scriptures–known as the Pentateuch–the Books of Moses, they mean that here Moses speaks of his understanding of God, and through Moses God speaks to his people.

Although Hebrew scripture takes different forms–poetry, history, law, and wisdom–the subject is always the same: the relationship between God’s people and their God. The human element in this relationship is significant and important to understand, for scripture is always understood to be a human response to the initiative of God. The scripture of the Jewish people does not simply record historical facts, but by its interpretation of history, the Jewish scripture seeks to ask and to answer the fundamental questions of human existence. Who am I? Why am I here? What is the purpose of life? What does it mean to be good? What is evil, and how do I deal with it? How do I deal with death? These are both individual questions and, with regard to the Jewish people, also public and communal questions. It must never be forgotten that it is a community of people chosen, beloved, and willful, to whom the Law, for example, is given, to whom the land is promised, and to whom a future is offered. The sacred literature of the Jewish people reflects this conviction, and that literature is therefore regarded as sacred because God is seen to be revealed in it. The determination, however, of what is sacred and what is scripture is a human and rational enterprise, and it tells us as much about the people of God as it tells us about God. As Wilfred Cantwell Smith points out in his book, What Is Scripture?, “Scripture is a human, and an historical fact. We may say: it is a human, and therein an historical, fact intimately involved with the movement, the unceasingly changing specificity of historical process, its grandeur and its folly.”

Thus the narrative history of Genesis, the legislative tedium of Leviticus, the books of history–Samuel, Chronicles, and Kings–the lyric, book of Psalms, the salacious, to some, Song of Solomon, the saga of Job, the wisdom of Proverbs, and the salutary story of Esther are all regarded as authoritative and inspired because each in its own way has been proven useful in the people’s attempt to understand themselves and their relationship to God. The Hebrew Bible is not merely a book of history or a book of devotion but a library of writings of proven worth, self-consciously composed, collected, and preserved as the repository of wisdom both human and divine. These writings reveal both the nature of the people who wrote and collected them, and the nature of their God. These writings are of course not God, and the writings themselves are not substitutes for God. That would be a violation of the first commandment, which forbids idolatry and false gods.

The Hebrew Bible is organized somewhat differently from what Christians call the Old Testament. The first five books are called The Law. The Prophets are divided into The Former Prophets, which include Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, The Latter Prophets, composed of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel, and those prophets called The Twelve, comprising Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. The third and final section of the Hebrew Bible is called simply The Writings, and includes Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Chronicles. This authoritative listing is referred to as a canon and evolved between A.D. 70 and 135 into its present form by a process of rabbinical councils. When Jesus refers to the Scripture, and New Testament Jewish Christians speak of the Law and the Prophets, it is this Bible of which they speak.

The Christians’ Book

When the early Christians, many of whom were Jewish, came to understand the Hebrew Bible as the necessary anticipation of their own Gospel, they reorganized the Hebrew Bible into four large categories: History, Poetry, the Major Prophets, and the Minor Prophets. Thus the elements of the Hebrew Bible were reconfigured into an “old” testament, which together with the authoritative Christian writings, the “new” testament, comprised the Christian Bible. The Christian scriptures were chosen from a wide range of early Christian writings, and the final product, the present canon, represents the consensus of usage and dignity confirmed by the earliest churches in A.D. 367. The New Testament is not arranged in chronological order. For example, all of the epistles of Saint Paul are older than any of the gospels. Recent scholarship places the Epistle of James as first by date, followed by I Thessalonians. To read the New Testament in chronological order is not necessarily superior to reading it in its canonical order, but it does allow us to follow the construction of the New Testament, and it reminds us once again that the New Testament is also the product of a self-conscious, human, and rational set of decisions. The canonical structure of the New Testament consists of History, which contains the four gospels and the Book of Acts; the Epistles of Paul, both those by him and those attributed to him; the General Epistles; and in a category all by itself, the Apocalypse, or the Revelation of John.

The Apocrypha is a category of books that tends to confuse most Protestants unfamiliar with the construction of the Bible and the political implications of its various translations and editions. The books in the Apocrypha are those books and fragments that do not appear in the Hebrew Bible but which were placed into the Latin Vulgate as part of the Old Testament. These books were to be found in the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible, but did not end up in the Hebrew canon. The Roman Catholic tradition regards these books as part of the canon, and since 1546, by decree of the Council of Trent, anathematizes anyone who says otherwise. Luther placed the Apocrypha between the two Testaments, and the English translations, while acknowledging that the apocryphal books were extra-canonical, found them to be useful and instructive. The Puritans decided that the Apocrypha was not inspired and thus removed it from their Bibles, and most modern editions of the King James Version, following the Puritan influence, exclude the Apocrypha, as do most of the newer English versions. The New English Bible, however, and of course versions approved for use by Roman Catholics, include it.

The place of the Bible in Christian theology is a subject of some complexity and goes back to the earliest debates of the forming Christian churches as to whether scripture or tradition took precedence in the determination of faith and practice. The dominance of the Bible in the Protestant traditions, particularly that part of Protestantism known as the Reformed Tradition, and in more modern times, the Evangelical branch of Protestantism, has generated what is generally known as a “high view” of scripture. This view has generated a number of slogans, which themselves are decidedly nonbiblical but which nevertheless convey certain doctrinal convictions by which the Bible is understood. The most famous of these is Luther’s sofa scriptura, which means “by scripture alone.” Under this view, scripture itself is the sole sufficient rule of conduct and belief for the Christian. Another principle, which is derived from this one, is the “authority of scripture,” and it is to that authority that the church and its members must submit. The scripture in this context is viewed very much like the federal Constitution of the United States, except, of course, that it cannot be amended.

Various other slogans designed to affirm the primacy of scripture actually in some cases make it harder to take scripture seriously. For example, in order to defend the integrity of scripture, some will say that either all is true, or all is false. This is meant to discourage picking and choosing from scripture the things that we like as opposed to the things that we dislike, but it strains credulity, and indeed the function of scripture, to argue that the Ten Commandments must be received in exactly the same fashion as the Song of Solomon, or that the Levitical Holiness Code is for Christians of the same order as the Beatitudes from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount Critics of the Bible are quick to point to the implausible parts, the petty anthropology attributed to the Hebrew God, for example, or Jonah and the fish, or the dubious morality by modern standards of certain of the patriarchs and kings of Israel, and on this basis argue that the morality of the Bible and its claims to authority are either suspect or irrelevant. The “all true or all false” argument works both to defend scripture and to defame it, and as a principle of interpretation probably does more harm than good.

In the next chapter we will discuss in more detail the question of interpretation. What we suggest now, however, are some broad principles which the reader of the Bible ought to bear in mind in becoming more familiar with the shape and content of scripture. These have to do with the character of the Bible, which is public, dynamic, and inclusive.

A Public

When I say that the Bible is public, I mean to say that it is a treasure that is held in common, it belongs to the community of believers and not to any one individual or to any one part of the community of believers. The Bible may have its private uses, and it may be used privately and as a source of great strength in private devotion, but its fundamental identity is as a resource, a treasure for the people. In the sacramental sense which Christians recognize from the Communion Service, the Bible too is the “gift of God for the people of God.” It is a very public record of the relationship between these people and their God, meant to be heard, understood, and remembered. When we realize the oral origins of scripture, and the fact that in the days before general literacy the only way that people became acquainted with the Bible was to hear it in the company of others, read aloud by one who could do so, then we realize that like the ancient tales of Homer and the histories of Greece and Rome, these were public stories that communicated public truths in the most public of ways. Even today in the churches of Christendom pride of place in the public liturgy is given to the public reading and hearing of the Bible.

The internal architecture of sacred space says it all. There is nearly always a splendid lectern upon which the book is placed, not simply for efficiency but for display as well. On the altar the gospel book is given a place of great honor, and in certain liturgical traditions the reading of the gospel is made all the more public and grand by a ceremonial procession of the book so that it can be read in the body of the church, and all turn toward it as it passes in procession. The pulpit itself is meant to be the place in which the public nature of the Bible is given its most explicit expression. A sermon that does not attempt to address the Bible is in fact not a sermon.

The public nature of the Bible is meant to have an impact upon public life. Again, it is not a secret of private vocation but a public proclamation of what can be discerned of God’s intentions for the creation from the witness and testimony of scripture. People should not be surprised, therefore, that Christians always want to translate their understanding of scripture and its demands into the public lives that Christians lead. The Bible is meant to play a role in society, as are Christians. This public dimension of the Bible invariably produces conflict, even in allegedly homogeneous Christian societies, and certainly in secular and pluralistic societies. This, however, is a conflict responsible Christians cannot avoid, and the working out of the proper relationship between the public dimensions of one’s biblical faith and one’s citizenship in a community that does not necessarily share or appreciate that faith is part of the inevitable and uneasy burden that every responsible Christian must shoulder. The early Christian martyrs would have lived to ripe old ages had they not found it necessary to proclaim their biblical convictions in public. To try to create a “Christian society” where there is no risk to the public nature of the Bible and the faith that cherishes it is a form of arrogant escapism. The Bible is a public book, and as such will always give offense. Christians who take the Bible and themselves seriously have to be prepared for that.

A Living Text

The second thing to be remembered about the Bible, as we proceed in our thinking about it, is that it is dynamic, living, alive, lively. “For the word of God is living and active, sharper than a two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and spirit, or joint and marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart.” (Hebrews 4:12) This means that behind the letter of the text is the spirit that animates it, the force that gave it and gives it life. Thus there is something always elusive about the Bible. This fixed text has a life of its own, which the reader cannot by some simple process of reading capture as his or her own. The dynamic quality of scripture has to do with the fact that while the text itself does not change, we who read that text do change; it is not that we adapt ourselves to the world of the Bible and play at re-creating it as in a pageant or tableau “long ago and far away.” Rather, it is that the text actually adapts itself to our capacity to hear it. Thus we hear not as first-century Christians, nor even as eighteenth-century Christians, but as men and women alive here and now. We hear the same texts that our ancestors heard but we hear them not necessarily as they heard them, but as only we can. Thus the reading and the hearing of scripture are for Christians in each generation a Pentecostal experience. That experience is described in the Book of Acts as the great moment when the Holy Spirit descended upon the great and diverse crowd of believers in Jerusalem. The writer of Acts goes to great lengths to describe the diversity of that crowd, people from all over the known world who had little in common but Jerusalem as the object of the pilgrimage. They all were filled with the Holy Spirit, and began to speak in tongues.

Now often the emphasis here is placed on the ecstatic utterance, the Spirit-filled glossolalia, the exotic sounds of people under an extraordinary spell. Anyone who has ever experienced an outbreaking of speaking in tongues knows the exotic nature of that experience. What must be emphasized, however, and what is in fact the point of the writer of Acts, is that the people understood what was going on, and even more to the point, they understood in their own languages: not a paraphrase, not a delayed interpretation, not even a translation; they understood in their own languages. “We hear them telling in our own tongues,” says the writer of Acts in Chapter 2, verse 11, “the mighty works of God.”

The dynamic aspect of the Bible has to do with this quality of communication–not simply out of context or beyond context, but within our own singular and unique context–of the timeless and the timely message of the Bible. Christians believe that this dynamic quality is attributable directly to the power of the Holy Spirit, the agent of Pentecost. In other words, all our scholarship and research, our linguistic and philological skills, the tools of every form of criticism available to us, are merely means by which the living spirit of the text is taken from one context and appropriated totally into ours. The history of interpretation, perhaps the most useful field in which to study the dynamic dimension of scripture, bears witness to this in every age. In this sense, then, scripture is both transformed and transformative; that is to say, our understanding of what it says and means evolves, and so too do we as a result. This transformation does not always repudiate what was before, but it does always transcend it. The Buddhists say, “Seek not to follow in the footsteps of the men of old; rather, seek what they sought.” To understand the dynamic aspect of scripture, we must appreciate the fact that “what they sought” seeks us, and in fact, “what they sought” is apprehendable to us in terms and times that we can best understand. So in the Bible we handle lively things, which means that we must be subtle, supple, and modest, all at the same time.

An Inclusive Word

The third and final landmark for those on this pilgrimage, in which we try to make sense of the Bible, is the fact that in addition to being both public and dynamic, the Bible is also inclusive. That is to say, it has the power to draw all people unto itself. Historically, we see the ever-widening circle of the Bible’s appeal, and we can perhaps explain that by the cultural developments that moved out and beyond the provincial Mediterranean origins of the Bible into the Greco-Roman world, and then into the West, and then throughout the whole world. That, however, is simply a map maker’s view of the matter. What is more significant to observe, and indeed more profound, is the fact that people and cultures foreign to the people and cultures of the Bible find themselves drawn to the Bible and understand it not as somebody else’s book made available to them as an act of charity, conquest, or missionary endeavor, but as their own book, theirs legitimately and on their own terms. In the story of the Jewish patriarchs, non-Jews see themselves. In God’s particular activity in Jesus Christ, people beyond the little world of primitive Jewish Christianity see themselves and their story included in God’s activity. When in John’s gospel (John 10:16) Jesus says, “And I have other sheep, that are not of this fold; I must bring them also, and they will heed my voice. So there shall be one flock, one shepherd,” this is a great mandate for inclusivity which these “other sheep” recognize. As Jesus himself included among his own companions winebibbers, prostitutes, men and women of low degree, people who by who they were, by what they did, or from where they were excluded, so too does the Bible claim these very people as its own.

It is one of the unbecoming but unavoidable ironies of Christianity that Gentile Christians, who were excluded from the Jewish churches, and who in the times of the Roman persecution were themselves excluded from all hope in this life, should themselves become the arch practitioners of exclusion. Even centuries of Christian exclusivism, however, extending into our very own day, cannot diminish the inclusive mandate of the Bible, and the particular words of Jesus when he says, “Come unto me, all ye that labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” What Roman Catholic social theory teaches as the church’s “preferential option for the poor,” to the annoyance of Christians rich in the things of this world, is the same principle that extends the hospitality of the Bible, indeed preferential hospitality, to those who have in fact been previously and deliberately excluded. So the Bible’s inclusivity is claimed by the poor, the discriminated against, persons of color, homosexuals, women, and all persons beyond the conventional definitions of Western civilization.

The Bible is not inclusive simply in the abstract and in principle. It is inclusive in particular. Your story is written here, your sins and fears addressed, your hopes confirmed, your experiences validated, and your name known to God. The most reassuring conviction of the witness of scripture is that we are known by our own names. In Hebrew’s 2:12, Jesus says, “I will proclaim thy name to my brethren,” and the most telling moment of John’s account of the resurrection is when the risen Christ addresses the distraught and confused Mary Magdalene by her own name, and in hearing her name called, she discovers who the risen one is.

One of the great paradoxes of race in America is the fact that the religion of the oppressor, Christianity, became the religion of the oppressed and the means of their liberation. Black Muslims ask incredulously how any black person in America could possibly be a Christian, given the legacy of white Christianity. The answer, of course, is that if Christianity in America depended upon white Christians, there would be no right-minded black Christians. What is the case is that Christianity, and the Bible in particular, did not depend upon Christians for its gospel of inclusion, but upon God. Thus black American Christians do not regard their Christianity as the hand-me-down religion of their masters, or an unnatural culture imposed upon them and thus a sign of their continuing servitude. No! They understand themselves to be Christians in their own right because the Gospel, the good news out of which the Bible comes, includes them and is in fact meant for them. We will find that when we look at the life of the Bible, and the life of the world in which it is to be found, we discover that the heart of its public dimension, and indeed the source of its dynamism, in the principle of inclusion by which all of the exclusive divisions of the world are transcended and transformed.

In thinking about the Bible–its public nature, its dynamic, living qualities, and its inclusivity–as we try to make sense of it with mind and heart, we would do well to remember these three principal characteristics. They serve as landmarks, points of departure and of return, and they will guide us even as we seek guidance in opening the Bible.

Copyright 1997 Peter J. Gomes

William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Back to the top