Donald Trump’s Very Busy Court Calendar

The mass of motions, hearings, arguments, and gag orders related to the four criminal cases against Donald Trump can feel like a pile of jigsaw-puzzle pieces. They all fit together somehow, but the arrangement is unclear. In Florida, in the case involving Trump’s alleged hoarding of classified documents, Judge Aileen Cannon and Jack Smith, the special counsel, have been engaged in a bitter fight over jury instructions—even though there is as yet no jury, let alone a trial date. Meanwhile, the selection of actual jurors in the case related to a hush-money payment to the adult-film actress Stormy Daniels is due to begin on Monday in Manhattan. Once sworn in, that jury—the first to be impanelled in a criminal trial of a former President—might at last give some fixed form to the jumbled legal picture. Trump, as the defendant, must be present in court. After all the legal posturing, the action will finally get real.

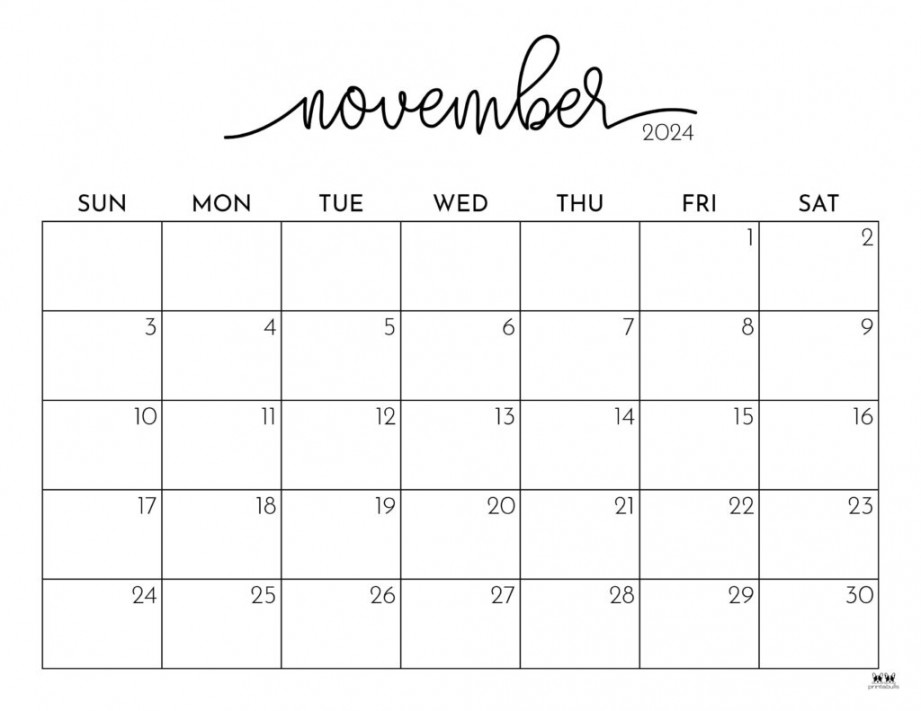

That’s the theory, anyway. But the focus will not only be on New York. In a ten-day period beginning on Tuesday, the second day of jury selection, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in two cases—Fischer v. United States and Trump v. United States—that could each undermine another indictment that Smith brought in Washington, D.C., involving Trump’s actions in the lead-up to the assault on the Capitol on January 6, 2021. The Fischer case will be heard first, on April 16th. It is a challenge to the Department of Justice’s use of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in hundreds of January 6th cases. That statute, which originally targeted corporate fraudsters who obstructed official proceedings by destroying records or other evidence, is the basis of two of the four charges against Trump in D.C.

Then, on April 25th, the Court will consider Trump’s outrageous assertion that, as a former President who was never convicted in a Senate impeachment trial, he is immune to criminal charges arising from acts within the “outer perimeter” of his official duties—a line that he believes encompasses his role in the events of January 6th. As an example of how confoundingly intertwined the cases are, a brief that Smith filed last week in the April 25th immunity case includes a footnote contending that, even if the Justices decide in the April 16th Fischer case that Sarbanes-Oxley can’t be used against most January 6th defendants, he should still be able to use it against Trump. (Smith’s argument is that Trump’s alleged solicitation of fake electoral certificates in seven states counts as classic meddling with evidence under Sarbanes-Oxley.)

And so, at the same time that Judge Juan Merchan, who is presiding over the New York trial, will be going through a list of forty-two questions with prospective jurors (What podcasts do they listen to? Have they ever been to a rally for Trump? How about to one for an “anti-Trump group”?), the Justices will be asking whether the D.C. trial should be gutted, or should even take place at all. One jury forward, two oral arguments back. It’s hard to know which way to look.

There is not so much a split screen as a tessellating one. Before the month is out, there will doubtless be more developments in Florida, too, and in the fourth criminal case against Trump, in Georgia, in which he is charged with conspiring to overturn the election results in that state. And there are the various ongoing civil proceedings, in which Trump is appealing orders that he pay more than half a billion dollars in damages and interest to New York and to the writer E. Jean Carroll.

Still, despite an almost constant frenzy of legal action, it can seem as though very little has actually happened. The New York trial is first because the other criminal cases are moving so slowly. Trump, who denies all wrongdoing, has, unsurprisingly, made use of whatever delaying tactics he can. (The Times recently calculated that he has already racked up more than a hundred million dollars in legal fees, which have largely been covered by donors and PACs.)

But there are additional reasons for the drawn-out pace. Judge Cannon, a Trump appointee who is new to the bench, has not been quick to rule on motions, and has issued orders that are confusing or have alarmed prosecutors because they suggest that she might be ready to accept some of Trump’s more farcical legal arguments. And although a number of the Florida charges, involving obstruction and making false statements, seem clear-cut, thirty-two counts rely on the Espionage Act, a statute with gray areas that have never been fully adjudicated by the Supreme Court, even without a former President as the defendant. Cannon was not entirely wrong when she referred, in a ruling last week, to the “still-developing and somewhat muddled questions raised in this criminal case.”

In the meantime, the Georgia prosecution has not quite emerged from the mess surrounding an attempt by Trump and some of his co-defendants to disqualify Fani Willis, the Fulton County district attorney. That effort stemmed from Willis’s romantic relationship with Nathan Wade, an outside lawyer whom she hired to work on the case. The judge found that he had no basis to remove her, but was so sharply critical of her choices, including her rhetoric, as to all but invite an appeal. That process is now under way. Given, though, that Willis brought the case with a sprawling RICO indictment against Trump and eighteen others (four have since pleaded guilty), it was never going to move quickly.

It is the New York case, then, that will first force the question of what exactly it means for Trump to be brought to justice. That concept can be writ small or large. There is a kind of justice in Trump’s being told to sit still and behave (and being sanctioned if he doesn’t), but comeuppance can’t be the main point. A case about hush money can’t really offer accountability for an attempted coup; nor can it fully address the understandable, widespread frustration that Trump has secured the Republican nomination despite the weight of the pending cases against him. And, while the New York charges carry the possibility of prison time, a conviction would not legally bar him from the Presidency. At this point, only the election in November can do that.

Trump’s worst characteristic may be his disdain for the rule of law; one of the best things a trial can do is to demonstrate the law at its fairest. The jury will have to weigh issues such as the credibility of a key witness, Michael Cohen, Trump’s former lawyer. One of the hardest questions that Merchan will ask prospective jurors is whether they can put aside everything else and decide the case based solely on what they see and hear in the courtroom. There’s a lot of noise outside. ♦