Surf boards v. school boards: NC’s school-calendar battle is being waged in court

A lawsuit in eastern North Carolina could force almost one-quarter of the state’s public school districts to start their school years later than they’d like in 2025 and beyond — a legal battle that is causing consternation among coastal business and local education officials.

About 27 of the state’s 115 school systems are expected to start their upcoming school year before Aug. 26 — the date state law says is the earliest they can start.

Many of these renegade districts have done it before — including the 2023-24 school year — without permission and without repercussion.

But their ability to do so beyond this year could depend on what happens in Carteret County, where a judge ordered a new county school calendar that complies with state law. The Carteret County School Board voted Thursday to appeal the decision.

The timing of summer break has long been a point of contention between tourism advocates and education groups in North Carolina.

The state’s current school calendar law is in line with the travel and tourism industry’s preference of a break that includes most of August — a period that favors businesses that benefit from the warmest months of the year.

But some education groups want more school-calendar flexibility. They say an early-August start would allow high school exams to be scheduled before winter break. It also aligns with the community college calendar, making it easier for more high school students to get a head start on undergraduate work or occupational training.

The case against the Carteret board could set precedent for more counties to either set their calendars early or never do so again. Near the Triangle, it could eventually affect systems in Harnett, Sampson, Person, Lee and Granville counties, and Clinton City Schools, which plan to start earlier than the law allows this year.

‘Uncharted waters’

The Carteret case was brought in April by a group of parents, two surf shops, and the owner of a fish market and restaurant who said they’d be “significantly harmed by the illegal calendar.”

They say the school board broke the law when it approved an Aug. 13 start date, despite knowing the law that stipulated Aug. 26 as the earliest start. The businesses say the school calendar law helps them plan, staff and run their businesses.

“The loss of revenue that would occur to the businesses from a shortening of the summer season would be significant,” they said in their complaint, which also warned that an early school start would depress tax revenues to support public education.

The Carteret County School Board argues that restricting school start and end dates violates the state constitution’s promise of a “uniform” public education system. They contend hundreds of schools — including charters, innovation high schools, certain low-performing schools, and some schools in western North Carolina — don’t have to follow the calendar law. The Carteret board argues that its system should be afforded the same flexibility, and that their early start date would help students take community-college classes that tend to start in early August.

The board expects to consider a more compliant calendar later this summer if the appeal doesn’t break its way.

As the appeal works through the courts, lawyers question whether other school systems will be affected.

“We have a judge’s ruling that says that a calendar that doesn’t comply with the calendar law is void,” said Mitch Armbruster, an attorney representing the plaintiffs in Carteret County. “I don’t know how other districts [will] react to that.”

Lacking a precedent-setting ruling from a higher court, enforcement of the calendar law could be inconsistent across the state, and it could come down to other local-level lawsuits.

“As for Carteret, it is their right to appeal, which I hope ends in a statewide appellate decision that will stop all the illegal calendars across the state, once and for all,” Armbruster said.

Armbruster last year represented Union County families who sued over an early-start calendar. Before a judge could rule, the school board reversed course.

“We’re kind of in uncharted waters for what enforcement would look like,” said Matt Ellinwood, a policy analyst at the North Carolina Justice Center’s Education and Law Project, a group that opposes the calendar law but doesn’t advocate for breaking it.

Ellinwood said the risks of not following the law are effectively unknown.

“You don’t want to do something that would harm students as a result by some kind of penalty,” he said.

The State Board of Education sends letters to the school boards and superintendents found to be in violation of the law. The letters don’t state what the consequences are but remind recipients of their responsibilities.

“You have a legal obligation to obey all state and federal laws,” the letters read. “In fact, you took an oath of office promising to do so. You must amend your calendar for the 2024-25 school year to stay with the legal boundaries imposed on you and your district by state legislation.”

Violating an oath of office to uphold the law is a misdemeanor under North Carolina law.

Mounting pushback

Hundreds of school leaders find exemptions every year through special designations for their schools, leaving other leaders to wonder why the law still matters. Charter schools, which are independent public schools, don’t have to follow the law; only traditional public schools without special academic or weather-related designations do.

“With respect to the real benefits of school calendar flexibility, traditional public school students are not provided equal opportunities with other schools, and this is wrong,” the Carteret County Board of Education said in a statement.

On Thursday, board members were animated with frustration by their predicament. They said any high school students wanting to take community college classes — which in North Carolina are often free and facilitated by their high schools for class credit — are 20 days behind in the classes under a calendar that aligns with the school calendar law, because the colleges start earlier but the high school students can’t. That drives down participation in those classes, they said.

The North Carolina Justice Center supports a change in part because of concern about summer breaks that are so long kids can forget what they’ve learned.

In the state legislature — where efforts to provide school systems with more control over start dates have failed in the past — chambers are divided. The House often supports local bills that allow school systems to be exempt from the calendar law, but the Senate won’t take up the bills. Senate President Pro Tempore Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, declined to say this week whether the Senate would take up the calendar issue.

“The school districts themselves should set a good example for the students under their charge and follow the law,” he said.

Armbruster argues that schools can still opt to become year-round, starting in early July, and contends that summers shortened by too many teacher workdays and breaks during the academic year are what spurred the law in the first place.

Carteret school board’s members said Thursday that switching to year-round schools would be a dramatic change for families.

“We’re not asking for July,” Board Member Travis Day said. “We’re asking for just a couple of weeks. There is no budging whatsoever about it, and it’s a shame.”

WRAL News sought comment from the school boards for the Harnett, Sampson, Person, Lee and Granville county systems, and the system in Clinton City, which are defying the calendar law. Most declined to comment. Some sent brief statements citing academic concerns as the reason why they or their school boards support their adopted calendars.

“The academic success of our students is one of our main priorities,” said Tracy Scruggs, a spokeswoman for Person County Schools. “Therefore, adopting a calendar that allows students to end the first semester before the Christmas break and also have close to the same amount of days in each semester seemed to be in the best interest of our students.”

In Granville County Schools, spokesman Stan Winborne said: “Our Board approved the 2024-25 school calendar based on what they felt was in the best interests of our students, as they always do.”

In Moore County, the school system surveyed parents, employees, students and community members on two different calendar types for the 2025-26 school year: the one bound by state law and one that would start two weeks earlier and end before Memorial Day.

Out of the more 1,000 people who responded — most of them parents — three-quarters preferred the early start calendar.

Still, the superintendent recommended against approving the early start calendar for the 2025-26 school year at an April meeting, and the school board instead approved the legal calendar on a slim 4-3 vote. Even those who voted for the legal calendar said they didn’t like it.

After calling the reasoning for the calendar law “hogwash,” Chairman Robert Levy told the board, “That lawsuit woke me up to understanding exactly the gravity of what we’re doing.”

He questioned the price of taking on a legal battle over the calendar.

“Are we going to spend the children’s money — $10,000, $20,000, $30,000, maybe $100,000 — defending a lawsuit and potentially be liable ourselves for disobeying the law?” Levy asked. “Or are we going to be honest with the public and say to the public, ‘We understand what you want, but we don’t have the power.’”

Other school systems have informally surveyed residents and found similar results.

Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools — the largest system set to defy the law next year — did so after school board members asked the system to survey the public on a calendar option that would start two weeks early.

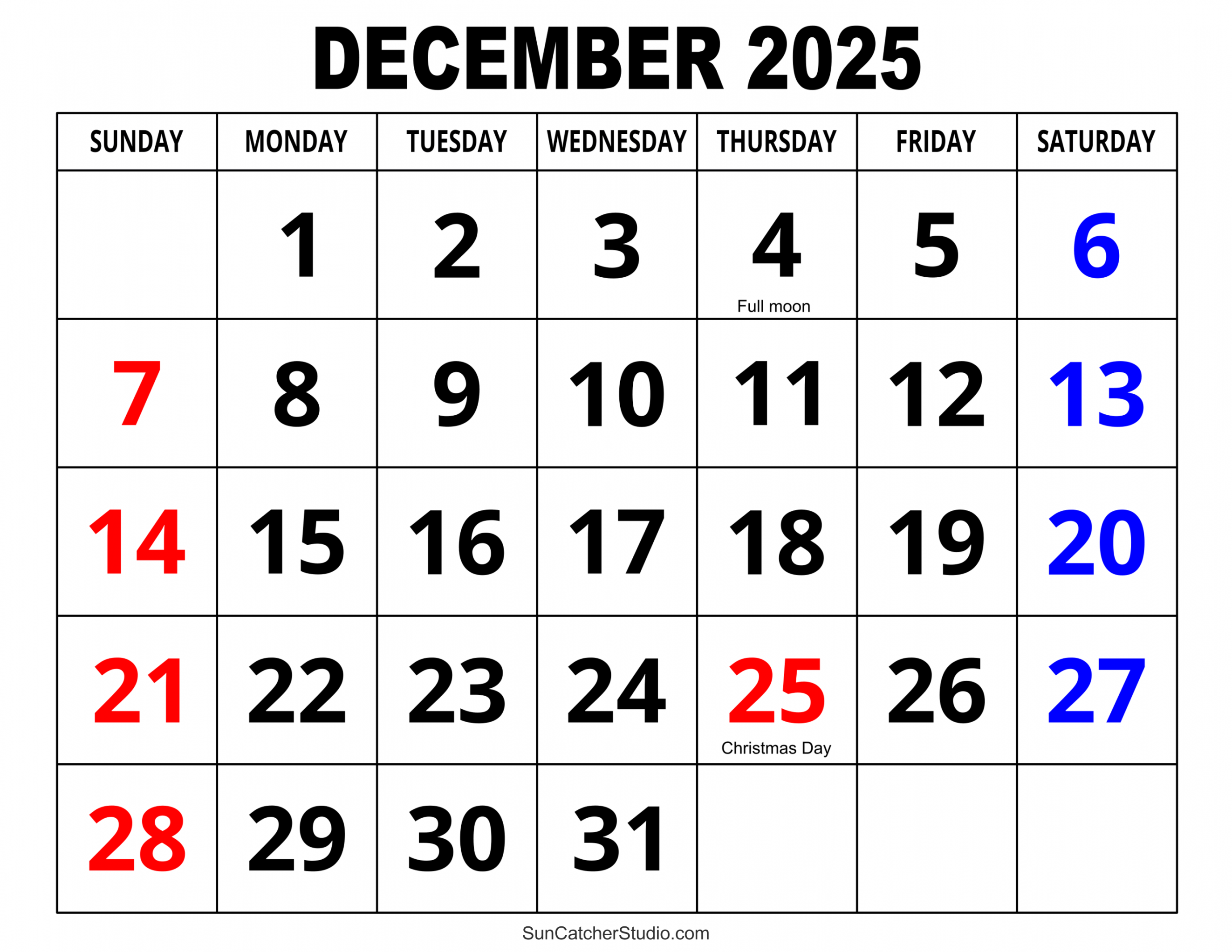

The system had not recommended such a calendar and has once again not recommended such a calendar for the 2025-26 school year. But in December, when the public was asked about the 2024-25 school year, they overwhelmingly preferred the early start calendar. That was about 3,000 of the more than 4,000 respondents — a mix of parents, staff and students.